With interactive gaming re-creations, head-to-head competitions, artifacts and a giant game of âPong,â the is every gamerâs dream.

Making a Museum

The museum, located inside the Frisco Discovery Center, opened its doors to the public April 2. It is the first museum in the United States to be solely dedicated to the history of the video game industry.

The concept of NVM was in the minds of founders John Hardie, Sean Kelly and Joe Santulli for years. The trio had been collecting video game artifacts and memorabilia throughout the last three decades.

Hardie, Kelly and Santulli first collaborated in 1999 at a gaming expo in Las Vegas when they brought their collections together and called it a museum. This annual event continued until 2002 when they started attending industry events, like the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) and the Penny Arcade Expo (PAX), as well.

In 2011, the team realized their traveling museum needed a permanent home.

âWe got to the point where weâre getting a little bit older, our stuff is getting a little worn out,â Santulli said. âPlus people were asking us questions like, âWhen do we get to see this on a regular basis? Why do we have to wait until once a year or go to industry events?ââ

Very shortly after, the trio met Randy Pitchford, CEO of Gearbox Software, who offered to collaborate on the effort.

âOur initial home we thought would be Silicon Valley,â Santulli said. âBut we needed a sponsor and a city that was ready to help up pay for the place.â

And Frisco was that place, offering the space and a $1 million in funding for the museum.

âFrisco was in a position to make it happen and they did,â Kelly said. âIt fit perfectly for this part of the city. They had the space already and they werenât really doing anything with it. Everything kind of fell together.â

Making a Mural

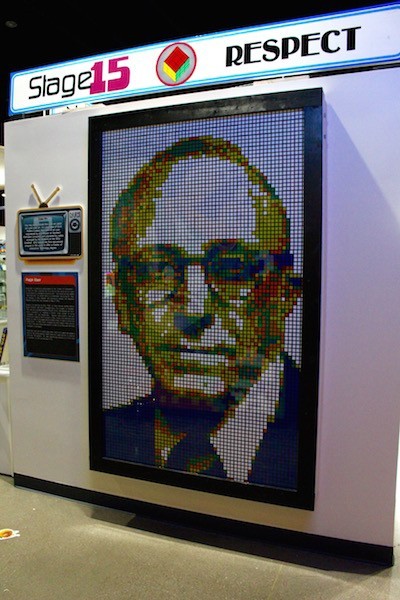

The next step came in designing and filling the space; this is where came into play to build a mural of Ralph Baer out of more than 600 Rubik Cubes.

Gary Brubaker, director of Guildhall, said the relationship with NVM began when Pitchford introduced them.

âIt was clear they had one of the most significant and sizable collections,â Brubaker said. âThe fit was natural as academia and museums improve each otherâs mission.â

Squirrel Eiserloh, game programmer/designer and Guildhall lecturer, said the Rubikâs Baer mosaic was originally the brainchild of the NVMâs founders.

âThe problem was layered and interesting,â Eiserloh said.

Eiserloh worked to design a program that would use only the six colors found on the Rubik Cubes that could be reconfigured periodically to show different images.

âHe, not surprisingly, had a number of anti-aliasing tricks from computer graphics to create a realistic picture from a very limited palette,â Brubaker said.

Eiserloh said they wrote a highly-adjustable custom program that takes a source photo and coverts it to a mosaic of Rubikâs Cube colors. The pattern was then printed across several pieces of paper.

âWe then had a small army of volunteers â kids, graduate students, and game industry professionals â help solve cubes for an entire afternoon,â Eiserloh said. âIt was quite amazing to watch come together.â

Students from Guildhall volunteered to work on the project by organizing the cubes on the paper before they were mounted into the mural. They were excited to not only work on the project, but also to be surrounded by the history of video games.

âSome students helped with the construction of the frame and mount as well,â Eiserloh said. âAll were pleased and proud at the finished product.â

The mural of Ralph Baer created by ÍćĹź˝ă˝ăGuildhall. Photo credit: Christina Cox